Cognitive Aspects of Skilled Typewriting

Free download. Book file PDF easily for everyone and every device. You can download and read online Cognitive Aspects of Skilled Typewriting file PDF Book only if you are registered here. And also you can download or read online all Book PDF file that related with Cognitive Aspects of Skilled Typewriting book. Happy reading Cognitive Aspects of Skilled Typewriting Bookeveryone. Download file Free Book PDF Cognitive Aspects of Skilled Typewriting at Complete PDF Library. This Book have some digital formats such us :paperbook, ebook, kindle, epub, fb2 and another formats. Here is The CompletePDF Book Library. It's free to register here to get Book file PDF Cognitive Aspects of Skilled Typewriting Pocket Guide.

Contents:

The Inner Loop is Informationally Encapsulated Our outer-loop inner-loop theory assumes that the intelligence required to type text is divided between the loops. The outer loop is concerned with language generation and comprehension, and its job is to produce a string of words to be typed.

The inner loop is concerned with translating words into letters, finger movements, and keystrokes, and its job is to produce a series of keystrokes on the keyboard. With this division of labor, the outer loop does not need to know what the inner loop does. It only needs to provide the inner loop with words to be typed, one at a time. We believe that the outer loop does not know what it does not need to know. The inner loop is informationally encapsulated Fodor, , so the outer loop does not know how the inner loop does what it does.

Subscribe to RSS

The Outer Loop Does Not Know Which Hand Types Which Letter The outer loop knows which words must be typed and it is able to spell the words, but it usually does not break words down into letters before passing them to the inner loop. The previous section summarized the evidence suggesting that the outer loop passes whole words to the inner loop, and the inner loop breaks the words down into letters and assigns the letters to particular hands and particular keyboard locations.

This division of labor suggests that the outer loop does not know which hand types which letter but the inner loop does it must because it types letters correctly. Hierarchical Control of Cognitive Processes: The Case for Skilled Typewriting 13 Logan and Crump showed that the outer loop does not know which hand types which letter by having typists type only the letters assigned to one hand. This was very disruptive, as you can confirm for yourself by typing only the right-hand letters in this sentence. In one experiment, we had typists type whole paragraphs and told them to type only the left-hand letters or only the right-hand letters.

When the same typists typed the same texts under instructions to type normally i. Our two-loop hypothesis resolves the paradox by proposing that the inner loop is informationally encapsulated. Our research provides one explanation for the disrup- tion: performance must slow down so the outer loop can observe the details, and that disrupts timing and the fluency of performance. Our intuitions as typists tell us we have little explicit knowledge of letter location, yet our fingers find the correct loca- tions five to six times per second. We suggest that this is also a consequence of the division of labor between outer and inner loops and another example of encapsulated inner-loop knowledge.

In this case, there may be stronger motivation for encapsulating knowledge about letter location in the inner loop: the locations of letters in words rarely correspond to the locations of letters on the keyboard e. Crump order on the screen and on the keyboard. Encapsulating knowledge about letter location and communicating information about letters through the intermediary representations of words may reduce the costs of stimulus— response incompatibility.

We asked typists to imagine that they were standing on a key on the keyboard e. In a second experiment, Liu et al. Absolute distance error—the unsigned distance between the correct location and the location to which they dragged the key—was 81 mm for typists who imagined the keyboard, 58 mm for typists who saw the keyboard, and 54 mm for typists who typed the letters on a keyboard covered by a box. This experiment allowed us to compare the relative precision of explicit and implicit knowledge of letters on the keyboard.

In the explicit judg- ments, the standard deviation of the distance between the correct and judged location signed distance error was 28 mm. To estimate the standard deviation of the distance between correct and judged location in implicit judgments, we assumed that location was represented implicitly as a bivari- ate normal distribution centered on the key and that the percentage of correct responses reflected the proportion of the distribution that fell within the boundaries of the key.

Cognitive Aspects of Skilled Typewriting by W. E. Cooper, Paperback | Barnes & Noble®

We estimated a z score for the radius of the bivariate normal distribution by taking the square root of the 93rd quantile of a chi-square distribution with 2 degrees of freedom. The quantile was 5. The square root corresponds to a z score of 2. This analysis underestimates the difference in precision because it assumes that all typing errors are misplaced keystrokes, and that is not the case.

Insertions, deletions, and transpositions are more common Lessenberry, ; Logan, The standard deviation of implicit knowledge of key location may be much smaller than 4. Together with the evidence for selective influence and limited word-level communication between loops, the evi- dence for informational encapsulation makes the case for hierarchical con- trol even stronger. The Outer Loop and the Inner Loop Rely on Different Feedback Feedback loops are defined in terms of the goals they are intended to achieve, the operations they carry out in order to achieve them, and the feedback they evaluate to determine whether or not the operations were successful.

- Simulating a Skilled Typist: A Study of Skilled Cognitive-Motor Performance.

- Fenimore Cooper.

- A Hot-Eyed Moderate: Essays.

- Cognitive Aspects of Skilled Typewriting - Semantic Scholar.

- A fundamental cognitive skill for daily life!

- Bullying: Implications for the Classroom (Educational Psychology).

TOTE units evaluate feedback in the test phase by comparing the goal state and the current state. Thus, feedback can be identified by discovering the goal state and the current states—mental or physical—to which the TOTE is sensitive. Different TOTEs should be sensitive to different feedback. This suggests that the outer and inner loops should be sensitive to different kinds of feedback, and the feedback for the inner loop should be finer-grained than the feedback for the outer loop. We have two lines of evidence supporting this proposition. Our research was motivated in part by dueling intuitions from our own experience as typists about the role of the keyboard in skilled typing.

On the one hand, we find it very difficult to type in the air or on a tabletop without a keyboard to support our typing.

Passar bra ihop

This suggests that the feel of the keyboard is essential. On the other hand, we believe that typing is a general skill that can be transferred readily to new keyboards.

This volume marks the 75th anniversary of the publication of William Book's The Psychology of Skill, in which typewriting received its first large-scale. Cognitive Aspects of Skilled Typewriting por W. E. Cooper, , disponible en Book Depository con envío gratis.

Otherwise, we would be reluctant to buy new computers or switch between keyboards on desktops and laptops. However, commercial keyboards are very similar, with keys of similar sizes at similar distances in similar layouts. Transfer outside of these familiar parameters may be difficult. Ultimately, the ques- tion is empirical, so we designed an experiment to test it. First, we removed the keys from a regular keyboard and had typists type on the rubber buttons underneath them. Then, we removed the buttons and had typists type on the flat plastic panel underneath the buttons, in which the circuitry is embedded.

This removes the resistance of the keyboard as well as the feel of the keys. Finally, we tested the typists on a commercially available laser projection keyboard that projected a life-size image of the keyboard on a tabletop. Like the flat keyboard, the laser keyboard removes the feel of the keys and the resistance of the buttons.

Similar effects were found in typing paragraphs.

Recommended for you

Typing speeds were 76, 52, 30, and 43 words per minute on the regular, button, flat, and laser keyboards, respectively. These large disruptions suggest that the feel of the keyboard is an important source of feedback that supports inner-loop performance. As a further test of the importance of feedback from the keyboard, we had 61 typists place their fingers on a blank piece of paper as they would if they were resting on the home row, and we traced the outline of their fingertips.

The outline was curved, following the natural contour of the fingertips, and not straight, as it would be if the fingers were resting on the keyboard. The mean discrepancy from a straight line was This suggests that the feel of the keyboard is important in maintaining the proper alignment of the fingers on the keys. The Outer Loop Relies on the Appearance of the Screen An important function of a feedback loop is to detect errors in performance. The processes that implement the operate phase of a TOTE may not always reduce the discrepancy between the current state and the goal state.

Some- times they increase it. In tasks like typewriting, operations that increase the discrepancy between the current state and the goal state produce errors such as typing the wrong letter, omitting a letter that ought to be typed, or typing the right letters in the wrong order Lessenberry, ; F. Logan, Typists must detect these errors and correct them Long, ; Rabbitt, The two-loop theory of typewriting claims that the outer loop and inner loop process different kinds of feedback, which implies that the two loops detect errors in different ways.

The outer loop generates a series of words to be typed and so should monitor the accuracy with which words are typed. We suggest that it monitors the computer screen for the appearance of the intended word.

If the intended word appears as it should, the outer loop assumes that it was typed correctly and moves on to the next word. If the intended word does not appear as it should, the outer loop assumes it was an error and asks the inner loop to make the screen look right. The inner loop generates a series of keystrokes and monitors proprioceptive and kinesthetic feedback to ensure that the right fingers moved to the right locations and struck the right keys.

If the movements match intentions, typing should remain fast and fluent. If there is a mismatch, typing should slow down or stop. To test these claims, Logan and Crump had typists type single words and created mismatches between what typists actually typed and what appeared on the screen. We corrected errors that typists made, so the screen matched their intentions but their motor behavior did not, and we inserted errors that typists did not make, so their motor behavior matched their intentions but the screen did not. To measure outer-loop error detection, we had typists report whether or not they typed each word correctly.

We assumed that the outer loop monitors the appearance of the screen and so would report corrected errors as correct responses and inserted errors as actual errors, showing cognitive illusions of authorship. In another experiment, we told typists we would correct some errors and insert some errors, and we gave them four alterna- tive posterror responses correct, error, corrected error, inserted error. We found cognitive illusions of authorship for corrected errors: typists were as likely to call them correct responses as corrected errors.

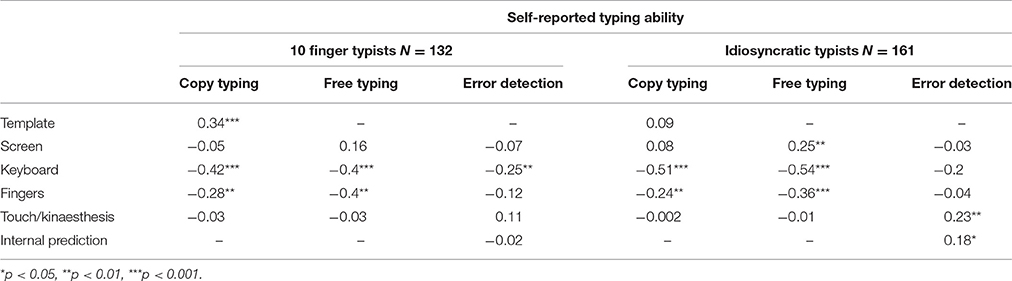

Stevens, A. The group that learned to write letters by hand were better at recognising them than the group that learned to type them on a computer. People undoubtedly write more than they suppose, but one thing is certain: with information technology we can write so fast that handwritten copy is fast disappearing in the workplace. Write a Review. TABLE 3. Hopstaken, J.

We measured inner-loop error detection by assessing posterror slowing. We found posterror slowing for actual errors and corrected errors but no posterror slowing after inserted errors.

- Your Answer!

- Geometry II (Universitext).

- Cognitive Aspects of Skilled Typewriting | W. E. Cooper | Springer.

- Low-Power Low-Voltage Sigma-Delta Modulators in Nanometer CMOS (The Springer International Series in Engineering and Computer Science).

- Account Options!

Thus, the inner loop knew the truth behind the illusion of authorship. The contrast between explicit error reports and posterror slowing sug- gests a dissociation between outer-loop and inner-loop error detection. Explicit reports of correct responses occurred both with actual correct responses, which produced no posterror slowing since there were no errors , and with corrected errors, which produced posterror slowing.

Explicit reports of erroneous responses occurred both with actual errors that exhibited posterror slowing and with inserted errors that exhibited no posterror slowing. This dissociation provides further support for our dis- tinction between the outer loop and the inner loop. Reliance on different feedback is strong evidence that the two loops engage in different computations, which supports the claim that they are different processes. Together with the evidence for selective influence, limited word-level communication, and informational encapsulation, the evidence for reliance on different feedback makes a strong case for hierarchical control in typewriting.

Beyond Typewriting 8.

- Flight Handbook - Navy Model S2F-1, -2 Aircraft [AN 01-85SAA-1]

- Computational Fluid Dynamics 2010: Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Computational Fluid Dynamics, ICCFD6, St Petersburg, Russia, on July 12-16, 2010

- The Palgrave Handbook of Prison Ethnography

- Functional analysis: Surveys and recent results

- Male Sexual Function: A Guide to Clinical Management 2nd ed (Current Clinical Urology)

- The Chemistry of Pyrroles

- Cultural semiotics, Spenser, and the captive woman