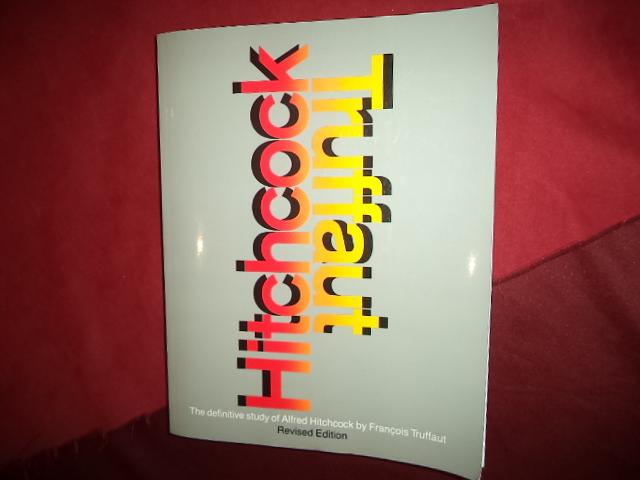

Hitchcock: A Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock (Revised Edition)

Free download. Book file PDF easily for everyone and every device. You can download and read online Hitchcock: A Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock (Revised Edition) file PDF Book only if you are registered here. And also you can download or read online all Book PDF file that related with Hitchcock: A Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock (Revised Edition) book. Happy reading Hitchcock: A Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock (Revised Edition) Bookeveryone. Download file Free Book PDF Hitchcock: A Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock (Revised Edition) at Complete PDF Library. This Book have some digital formats such us :paperbook, ebook, kindle, epub, fb2 and another formats. Here is The CompletePDF Book Library. It's free to register here to get Book file PDF Hitchcock: A Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock (Revised Edition) Pocket Guide.

Contents:

- Hitchcock Definitive Study Alfred by Francois Truffaut - AbeBooks.

- Listen to 12 Hours of François Truffaut Interviewing Alfred Hitchcock for Free;

- Formats and Editions of Hitchcock : [the definitive study of Alfred Hitchcock] [giuliettasprint.konfer.eu].

- Hitchcock Definitive Study Alfred by Francois Truffaut;

Unable to Load Delivery Dates. Enter an Australian post code for delivery estimate. Link Either by signing into your account or linking your membership details before your order is placed.

Hitchcock: A Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock Paperback – 13 Jun Francois Truffaut (Author) This is one of the most thorough reviews of a director's work ever produced, thanks to Truffaut's idolising Hitchcock. Hitchcock (Revised Edition) [Francois Truffaut, Helen G. Scott] on giuliettasprint.konfer.eu Hitchcock: A Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock and millions of other books.

Description Product Details Click on the cover image above to read some pages of this book! Story Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles Stephen King at the Movies. Bond Behind the Scenes. Coreyography A Memoir.

Popular Searches books recommended by oprah hitchcock truffaut book list of books by author nick bantock testimony robbie robertson book woodworking scroll saw. Item Added: Hitchcock. View Wishlist. Our Awards Booktopia's Charities. Are you sure you would like to remove these items from your wishlist? Balachov, Carradine, Benson, and Tolmachef.

One of the charges frequently leveled at Hitchcock is that the simplification inherent in his emphasis on clarity limits his cinematic range to almost childlike ideas. To my mind, nothing could be further from the truth; on the contrary, because of his unique ability to film the thoughts of his characters and make them perceptible without resorting to dialogue, he is, to my way of thinking, a realistic director. Hitchcock a realist?

In cinema, as on the stage, dialogue serves to express the thoughts of the characters, but we know that in real life the things people say to each other do not necessarily reflect what they actually think and feel. This is especially true of such mundane occasions as dinner and cocktail parties, or of any meeting between casual acquaintances. If we observe any such gathering, it is clear that the words exchanged between the guests are superficial formalities and quite meaningless, whereas the essential is elsewhere; it is by studying their eyes that we can find out what is truly on their minds.

Let us assume that as an observer at a reception I am looking at Mr.

See a Problem?

Y as he tells three people all about his recent holiday in Scotland with his wife. By carefully watching his face, I notice he never takes his eyes off Mrs. Now, I move over to Mrs. Obviously, the substance of that scene is not in the dialogue, which is strictly conventional, but in what these people are thinking about.

Merely by watching them I have found out that Mr. Y is physically attracted to Mrs. X and that Mrs. X is jealous of Miss Z. From Hollywood to Cinecitta no film-maker other than Hitchcock can capture the human reality of that scene as faithfully as I have described it. And yet, for the past forty years, each of his pictures features several such scenes in which the rule of counterpoint between dialogue and image achieves a dramatic effect by purely visual means. Hitchcock is almost unique in being able to film directly, that is, without resorting to explanatory dialogue, such intimate emotions as suspicion, jealousy, desire, and envy.

And herein lies a paradox: the director who, through the simplicity and clarity of his work, is the most accessible to a universal audience is also the director who excels at filming the most complex and subtle relationships between human beings. In the United States, the major developments in the art of film direction were achieved between and , primarily by D. Most of the masters of the silent screen who were influenced by him, among them von Stroheim, Eisenstein, Murnau, and Lubitsch, are now dead; others, still alive, are no longer working.

Considering the fact that the Americans who entered the film medium after have barely scratched the surface of the limitless potential Griffith opened up, I believe it is not an overstatement to conclude that, with the notable exception of Orson Welles, no major visual sensibility has emerged in Hollywood since the advent of sound. If the cinema, by some twist of fate, were to be deprived overnight of the sound track and to become once again the art of silent cinematography that it was between and , I truly believe most of the directors in the field would be compelled to take up some new line of work.

One wonders, not without melancholy, whether that legacy will survive when they retire from the screen. Among the big Hollywood names, the Oscar collectors, there are undoubtedly many men of talent. And yet, as they switch from a Biblical opus to a psychological western, or from a war epic to a comedy of manners, how can we look upon them as anything else than simple craftsmen, carrying out instructions, dutifully falling in line with the commercial trends of the day?

Why establish any distinction between these motion-picture directors and their counterparts in the theater when, year in and year out, they follow a similar pattern, going from the screen version of a William Inge play to an Irwin Shaw best seller, while working on an adaptation of the latest Tennessee Williams? Unlike the film author, who is motivated by the need to introduce his own ideas on life, on people, on money and love into his works these men are mere show-business specialists, simple technicians. Are they great technicians? Of what does their work actually consist?

Hitchcock: A Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock

They set up a scene, place the actors within that setting and then proceed to film the whole of that scene, which is substantially dialogue, in six or eight different ways by varying the shooting angle, from the front, the side, a high shot, and so on. Afterward, they do it over again, this time varying the focus. The next step is to film the whole scene, first using a full shot, then a medium shot, and finally in close-up.

This is not to suggest that the Hollywood greats, as a whole, do not deserve their reputations. To give credit where it is due, most of them have a specialty, something they do exceptionally well. Some excel at getting a superior performance from their stars, while others have a flair for bringing new talent to light. Some directors are brilliant storytellers and others have a remarkable gift for improvisation. Some are excellent at battle scenes and others have a knack with the intimate comedy genre.

If Hitchcock, to my way of thinking, outranks the rest, it is because he is the most complete film-maker of all. He is not merely an expert at some specific aspect of cinema, but an all-round specialist, who excels at every image, each shot, and every scene. He masterminds the construction of the screenplay as well as the photography, the cutting, and the sound track, has creative ideas on everything and can handle anything and is even, as we already know, expert at publicity! Because he exercises such complete control over all the elements of his films and imprints his personal concepts at each step of the way, Hitchcock has a distinctive style of his own.

He is undoubtedly one of the few film-makers on the horizon today whose screen signature can be identified as soon as the picture begins. His style can be recognized in a scene involving conversation between two people, in his unique way of handling the looks they exchange, and of punctuating their dialogue with silent pauses, by the simplified gestures, and even by the dramatic quality of the frame. Just as unmistakably Hitchcockian is the art of conveying to the viewer that one of the two characters dominates, is in love with, or is jealous of, the other.

It is the art of creating a specific dramatic mood without recourse to dialogue, and finally the art of leading us from one emotion to another, at the rhythm of our own sensitivity.

- Navigation menu.

- Download and Listen to Hitchcock Interviews by Truffaut for Free. - mentorless.

- Hitchcock/Truffaut - Wikipedia.

- Download and Listen to Hitchcock Interviews by Truffaut for Free.;

Psycho is a picture that rallied vast audiences throughout the world; yet, in its savagery and uninhibited license, it goes much further than those daring mm. When a director undertakes to make a western, he is not necessarily thinking of John Ford, since there are equally fine movies in the genre by Howard Hawks and Raoul Walsh.

Overt or subconscious, bearing either on the style or the theme, mostly beneficial, occasionally ill-advised, this influence is reflected in the works of film-makers who are vastly different from each other:. But inasmuch as his achievements have, until now, been grossly underrated, I feel it is high time Hitchcock was granted the leading position he deserves. Only then can we go on to appraise his work; indeed, his own critical comments in the pages that follow set the tone for such an objective examination. British critics, who at heart have perhaps never forgiven Hitchcock for his voluntary exile, still marvel—and rightly so—at the youthful, spirited vigor of The Lady Vanishes, which he made thirty years ago.

Shop by category

In a critical essay published in Film Quarterly, Charles Higham describes Hitchcock as a practical joker, a cunning and sophisticated cynic. He refers to his narcissism and its concomitant coldness and to his pitiless mockery, which is not a gentle mockery. According to Higham, Hitchcock has a tough contempt for the world and his skill is most strikingly displayed when he has a destructive comment to make. Though he raises an important point, I feel Mr. A strong person may be genuinely cynical, whereas in a more sensitive nature, cynicism is merely a front.

He is not involved in life; he merely contemplates it.

Hitchcock: A Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock

In making a film like Hatari, Howard Hawks gratifies his dual passion for hunting and for cinema. In the life of Alfred Hitchcock there is but one passion, which was clearly expressed in his reply to a moralizing attack on Rear Window. Nothing, he said, could have prevented my making that picture, because my love for cinema is stronger than any morality. If, in the era of Ingmar Bergman, one accepts the premise that cinema is an art form, on a par with literature, I suggest that Hitchcock belongs—and why classify him at all? In the light of their own doubts these artists of anxiety can hardly be expected to show us how to live; their mission is simply to share with us the anxieties that haunt them.

Consciously or not, this is their way of helping us to understand ourselves, which is, after all, a fundamental purpose of any work of art. Hitchcock , by Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol. Editions Universitaires, Paris, Hitchcock, you were born in London on August 13, The only thing I know about your childhood is the incident at the police station. Is that a true story? Yes, it is.